|

HISTORY AND THE NEW TESTAMENT

By

Jack Kilmon

Jesus is born.

The

date of Jesus' birth cannot be placed with certainty. One must do

a little historical detective work to sort out the biblical

references. This is assisted by Luke who mentions certain

personages whose history is known. First among these is Herod the

Great, King of Judea. Luke 1:5 places the announcement of the

birth of John the Baptist "…in the days of Herod, King

of Judea." The best historical evidence places the death of

Herod shortly after an eclipse occurring on the night of Sunday,

March 12/13, 4 BCE. and the Passover of Wednesday, April 11, 4

BCE. This corresponds to the year 750 A.U. of the Roman Calendar.

Jesus was therefore born prior to 4 BCE.

The second person mentioned by Luke for this detective story is

one "Cyrenius" who was Publius Sulpicius Quirinius,

Roman soldier, senator and consul under Augustus. In 6 CE

Quirinius was sent to Syria as legate along with Coponius who

would be the first prefect of Judea and a predecessor of Pontius

Pilatus. The registration and census of 6 CE is too late to be

connected with the birth of Jesus. Additionally, the registration

of 6 CE did not include the Galilee. This has long been a

stumbling block in the determination of the date of Jesus' birth

and many scholars merely assumed that Luke had made a mistake. In

1912,however, the discovery by W. M. Ramsey of a fragmentary

inscription at Antioch of Pisidia arguably established Quirinius

was in Syria on a previous occasion. (1) His role was more

military to lead a campaign against the Homanadenses, a tribe in

the Taurus Mountains. This is confirmed by Tacitus. This means

that Quirinius would have established a seat of government in

Syria, including Palestine, from the years 10 to 7 BCE. In this

position he would have been responsible for the census mentioned

by Luke. This census of 7 BCE would therefore have been the

"first" census taken when Cyrenius was governor (Luke

2:2) and the historically documented census of 6/7 CE was really

the second. There is further evidence of this first census of 7

BCE in the writings of Tertullian who records the census

"taken in Judea by Sentius Saturninus." (2) C. Sentius

Saturninus was Legate of Syria from 9 to 6 BCE. Another

inscription, the Lapis Tiburtinus, was found in 1764 near Tivoli

(Tibur). Composed after 14 CE, the inscription names an unknown

personage who was legate of Syria twice. The man is described as

having been victorious in war. There is considerable dissension

among scholars as to whether the unnamed person is Quirinius. I

think it is more likely that it refers to the famous consul and

soldier.

Scholars have debated about the historicity of this first census

since there is no record of it in the Roman archives. Their chief

argument is that Augustus would not have imposed a census for the

purpose of taxation in the kingdom of a client king like Herod.

Herod had his own tax collectors and paid tribute to Rome from

the proceeds. They further pose that the census in 6 CE was

imposed because Herod's nutty son Archelaus had been deposed and

Judea was placed under direct Roman rule. These are good

arguments.

As a layman, I am forced to go back to Luke and ask why he would

record an event that never took place. Luke was well educated

with diversified talents. He seems careful in his historicity

and, although very young at the time, may very well have met

Jesus. He knew and interviewed those who were closest to Jesus.

Some scholars think that the story of the first census and the

birth in Bethlehem is theologoumenon.

This is a term scholars use for that which expresses an event or

notion in language what may not be factual but supports,

enhances, or is related to a matter of faith. In other words, a

"white lie." I don't buy it in this case. There is no

advantage to matters of faith in the invention of a census of 6

BCE.

Some scholars argue that the early census was invented to support

a mythological birth in Bethlehem in support of Messianic

prophecy. We'll cover the Bethlehem issue below. As for the early

census, I am inclined to believe Luke and Tertullian (even though

Tertullian isn't one of my favorite characters). I can think of a

number of reasons based on the history of the time. Lack of

records is not evidence for or against an historical event.

Records are lost and destroyed, particularly those that are two

millennia old. Rome burned in 64 CE and there have been numerous

conflagrations and sackings of the city over the centuries. Could

Augustus had deviated from convention and imposed a census in

Syria/Palestine in 6 B.C.E? Of course he could. He was the

Emperor. Herod the Great was ill and, by all accounts of the

time, nuttier than a fruitcake. He who had once been an able and

effective administrator and builder, was now paranoid and

vicious. He had murdered most of his family, including his sons

and the wife he loved most. The joke in the Roman court by Caesar

himself was that one was safer being Herod's pig than Herod's

son. Josephus records in Antiquities of the

Jews, XVI, ix 3 that Augustus was furious

with Herod in 8 BCE and threatened to treat him no longer as a

friend (Client), but as a subject (subject to taxes).

I believe that the prudent and prudish Augustus, scandalized by

Herod's outrageous reputation and increasing madness, began the

movement toward making Judea a prefecture in 8 BCE and part of

that preparation was a registration. Caesar could have delayed

actual imposition of direct rule in deference to Herod's ill

health and the hope that his successor would not be as loony

toony. When Herod died and Archelaus turned out to be crazier

than his father, Augustus threw in the towel (or Toga) and made

Palestine a prefecture. He sent Quirinius as Legatus (a second

time) and Coponius as the first prefect. The census of 6 CE

therefore becomes the first census under direct Roman rule and

fell in schedule with the Roman census on a 14 year rotation. The

census of Jesus' birth, perhaps only a registration, became lost

in the archives. In this scenario, it would make sense to send

Quirinius back as Legatus since he presided under the previous

registration. Quirinius was no minor functionary. He was a Roman

senator of the Equestrian order and had been consul since 12 BCE.

He had won an insignia of triumph for the Homanadensian war and

had accompanied Caesar to Armenia in 3 CE. He died in 21 CE.(3)

Service in Palestine was not considered "prime duty" by

Roman functionaries but the governorship of Syria was one of the

most important positions in the Empire. The post was always given

to the most respected and capable of Imperial functionaries

chosen from the elite of Roman aristocracy. The Syrian Legatus

was the commander-in chief of the entire Roman East and

responsible for the Parthian border. I believe this Roman

soldier, senator and administrator, who had already served Caesar

well, returned to Syria as a personal favor for his

emperor/friend. I must, therefore, be an audacious layman and

disagree with the majority of New Testament scholars. I conclude

that Luke is accurate.

|

Augustus Caesar..this

youthful portrait in molded glass was issued On the occasion of

his election as princeps (first citizen) in 27 BCE. He was about

56 years of age at the birth of Jesus.

Jesus' birth in the year 7 BCE would conform with the statements

of Luke but what was the day of his birth?

Scholars are nearly unanimous

that Jesus' birth did not occur on December 25 and on this I do

agree. December 25 was the Roman festival day of Natalis

Invictus, the birth of the Sun. The emperor Constantine, contrary

to tradition, was not a Christian but an advocate of the cult of

Sol Invictus. More for political expediency than for religious

reasons, Constantine tolerated Jesus as an earthly manifestation

of Sol Invictus, the son god. Since Christian doctrine was being

promulgated by Rome, compromises were being made between

Christianity, Sol Invictus and Mithraism. Constantine saw this as

a way of maintaining harmony. An edict by Constantine in 321 CE

ordered the courts to be closed on the "venerable day of the

sun" and Sunday was chosen as the day of observance rather

than the traditional Saturday Sabbath. If not on Christmas day,

therefore, on what day was Jesus born?

The "Star of

Bethlehem," Fact or Fiction?

Many biblical scholars have long contended the story of the

"Star of Bethlehem" to be a myth, another of those

theologoumenons (there's that word again). Astrology played an

important role in the ancient Middle East, including the Jews. It

would not be uncommon to correlate some celestial event with the

birth of Jesus, just as the eclipse had been correlated to the

death of Herod and a comet with the assassination of Julius

Caesar in 44 BCE. No comets or Novae, "new stars," can

be associated by astronomers with the period of Jesus' birth.

Hence the source of the Star of Bethlehem remained a mystery or

was considered myth.

In Prague, in 1603, shortly before Christmas, the astronomer and

mathematician, Johannes Kepler, was making observations of the

stars through his rudimentary telescope. He was observing the

conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn in the constellation of Pisces.

The two planets had converged to look like one larger and new

"star." Kepler later remembered something he had read

by the Rabbinical writer, Abravanel (1437-1508). Jewish

astrologers maintained that when there was a conjunction of

Saturn and Jupiter in Pisces, the Messiah would come. In ancient

Jewish astrology, the constellation of Pisces was known as the

House of Israel, the sign of the Messiah. Jupiter was the royal

star of the house of David and Saturn was the protecting star of

Israel, the Messiah's Star

Since the constellation of Pisces was the point in the heavens

where the sun ended it's old course and began its new, it is

understandable why this conjunction would be viewed as a portent

of the Messiah.

Kepler concluded that he had found the "star of

Bethlehem" but his hypothesis was rejected. It was not until

1925 that the hypothesis was re-examined when references to this

conjunction were found in the cuneiform inscriptions of the

astrological archives of the ancient School of Astrology at

Sippar in Babylonia. Sippar was an ancient Sumerian city lying on

a canal which linked the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. It was a

very important commercial and religious center. Excavations at

the site of Abu-Habbah during the latter part of the 19th century

unearthed the remains of a temple and ziggurat dedicated to

Shamash and the ancient scribal School of Astrology. The most

important discovery were tens of thousands of clay tablets from

the school archives that dated from the Old Babylonian and

Neo-Babylonian periods. In 1925, the German Scholar P. Schnabel

found, among the endless cuneiform records of dates and

observations, a note on a conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn in

the constellation of Pisces. The position of Jupiter and Saturn,

converged in Pisces, had been recorded over a period of five

months in 7 B.C.E!! Calculations show that the conjunction was

observable three times over the course of the year, May 29,

October 3, and December 4.

The conjunction in Pisces is observable in the southern sky over

Judea and would sit directly over Bethlehem if one were observing

along the road leading from Jerusalem to Bethlehem. Matthew 2:2

stating "We have seen his star in the east" is a

mistranslation of the Greek phrase EN TH ANATOLH "in the

east" from the original wording which means idiomatically,

"the first light of dawn" (which

comes from the east) when the conjunction is

visible. The correlation of this celestial event with the first

visit of Quirinius and a preliminary registration in Syria is too

much of a coincidence for this layman to ignore. I must therefore

humbly and respectfully disagree with the majority of New

Testament scholars who again contend that the story of the Star

of Bethlehem is another of those little "white lies." I

conclude again, therefore, that the Gospel account is accurate.

Accepting the Star of Bethlehem as an historical fact, our

detective work gives us three possible dates for the birth of

Jesus, May 29, October 3, and December 4 in the year 7 BCE. I

would rule out May 29 as too early. Scholars also contend that

the Gospel account of the three "Wise Men" is another

of those theologoumenon white lies. If one were to accept the

story of the three magi

(astrologers), or at least three visitors who came to Judea based

on the astrological omen, as containing an element of fact, May

29 is too early. Why would "wise men," astrologers/magi

in Babylon care about a celestial event predicting the Jewish

Messiah? Christians are normally unaware that Babylon was as

important a center for Judaism as Jerusalem in the ancient world.

It is the center for the predominating Babylonian Talmud. It is

very likely that the "wise men" were scholars of the

School of Astrology in Sippar and likely of Jewish ancestry

dating to the mass deportations of Jews to Babylon in the 7th

century BCE. Steeped in their Jewish messianic hopes and in

astrology, these men would have been convinced that the birth of

the Messiah was imminent. Given their background, an expedition

to the Homeland would seem the most likely course of action for

validation of both their scholarly, astrological and religious

prognostication. These astrologers would have observed the first

conjunction on May 29 and then made preparations to travel to

Judea, arriving for the time of a predicted second conjunction.

October 3 intrigues me because it is within days of the time of

other recorded Roman censuses. Including the one in 6 CE.

December 4 would be too late for Shepherds to be tending their

flocks. These were usually brought in around the first of

November. I must therefore again, with all respect to the New

Testament scholars, disagree that the Gospel story of the Wise

Men from the East is fiction. In this historical detective story,

correlating the Gospel accounts of the registration with the

celestial phenomenon, I choose Saturday, 10 Tishri, 3755

(October 3, 7 BCE.) as the date of the birth of Jesus. Interestingly, that day was a Yom Kippur, the

Day of Atonement.

Where was Jesus Born?

The Infancy Narratives of Matthew and Luke often conflict. In the

second chapters of both gospels, each author supports Bethlehem

as the place of Jesus' birth. The overwhelming opinion of New

Testament scholars again is that this is another theologoumenon

(that's such a pretty word). These scholars claim that Jesus was

born in Nazareth and that the Bethlehem story was invented to

conform to Messianic expectations found in Micah 5:1:

"But thou, Bethlehem Ephratah, though thou be little among

the thousands of Judah, yet out of ye shall he come forth unto me

that is to be ruler in Israel; and his goings forth are from

ancient time, from days of old."

Old rabbinical expectations of the Messiah arising from Bethlehem

may also be reflected in the Midrash Rabbah

and in Berakoth 5a of

the Jerusalem Talmud. These writings, however, are much later

than the time of Jesus and may not necessarily reflect Jewish

expectations of the first century. In other words, it may not

have been that big of a deal at the time of Jesus nor in the

century following the crucifixion that the Messiah had to be born

in Bethlehem. Jewish polemic against Jesus in the latter half of

the first century featured attacks on his legitimacy but did

not deny his birth in the City of David. If

he had not been born in Bethlehem, I doubt if the rabbinic

polemicists would have let it lie. This layman must therefore

again disagree with many scholars and conclude that the Gospel

account is accurate. It is this layman's conclusion that:

YeSHUa bar YoSEF (Jesus) was born on Yom Kippur, October 3, 7 BCE

in the village of Bethlehem during a registration instituted by

Augustus on an occasion when he was enraged at Herod's behavior.

This registration was overseen by Publius Sulpicius Quirinius and

was a preliminary to a direct Roman taxation. The taxation from

this registration in 7/6 BCE was delayed as a result of Herod's

age and health. The even more outrageous behavior of Herod's

successor, Archelaus, who was deposed, and infighting among the

other Herodian scions, convinced Augustus to institute a

praefecture and the first official Roman census and taxation in 6

CE and to liquidate the estate of the deposed Archelaus.(4) It is

this official first

census in Syria that confuses scholars regarding the birth of

Jesus since Quirinius again was sent by Caesar as legate under

the new prefecture. Coponius accompanied Quirinius and was the

first prefect.

A Rebellion in Galilee during

Jesus' youth

The institution of Judea as a prefecture and the enactment of

this second registration

in preparation for the first

direct Roman taxation stimulated a revolt in the Galilee by one Judas

of Gamala who would be the founder of the

Zealot party. The Pharisaic party was divided and consisted of

two "houses." The House of Hillel followed the milder

and more liberal teachings of that great rabbinic sage (30 BCE

-10 CE) and the House of Shammai, the harsher and more

conservative opponent of Hillel. Jews in Galilee, angered by

Roman oppression and this new taxation, rallied under the banner

of Judas and Tsadok, a

deputy of the House of Shammai. They attacked the two Roman

legions sent from Syria to suppress the rebellion and were

soundly defeated. As a result, two thousand zealots, including,

Judas, were crucified and about 6,000 young Galileans were

deported to slavery in the western empire.(5)

Almost certainly this event had a considerable influence on the

young Jesus. It would have occurred at approximately the same

time that the Gospels record the 12 year old Jesus taking his

vows at the Temple. Friends of the family, as well as relatives,

may have been sent to slavery in the west. Most seem to have been

sent to Spain and Sardinia. Are these deported and enslaved

relatives and friends of Jesus' on his mind as "the lost

sheep of the house of Israel" (Mt. 10:6) and when John

(10:16) records him saying , "..and other sheep I have,

which are not of this fold; them also I must bring, and they

shall hear my voice?" One of the traditions of Apostolic

journeys is Jesus' own cousin, James, the "greater,"

the older of the sons of Zebedee, going to Spain and Sardinia.

Returning to Jerusalem for the Passover of 44 CE, James was

executed by Herod Agrippa. It is not inconceivable that Rome had

put James on Agrippa's "hit list" as a result of his

stirring "dissension" among the Jewish slaves. Tied

with the taxation and the resulting rebellion, the year 6 must be

considered an important influence on Jesus, promulgating his

later invectives against some of the Pharisees (the House of

Shammai) and certainly against the Sadducees who were Roman

collaborators and led by the Roman appointed High Priest.

Jesus' Childhood

The only mention of Jesus' childhood in the Gospels is the 12

year old Jesus at the temple (Luke 2:41-51). To those familiar

with the Jewish customs and practices of the time, Y'shua had

reached the age of making vows

(6)and the age of discrimination.(7)

We know nothing about the rest of the childhood of Jesus. Known

aspects of the cultural, social, family, and religious habits of

first century Judea and Galilee allow us to make educated guesses

about the upbringing and development of the young Jesus. We can

be certain that he struggled with the same physical, sexual,

intellectual and spiritual matters that are normal to the

maturation of all young males throughout human history. In this

all too familiar journey from child to adult, he would have

developed a sense of his identity, a definition of self. Whether

that early sense of self would include a concept of his own

ultimate purpose and destiny, we cannot know. All we can do is

look at those internal family elements typical for a Galilean

family of the time and the external environment of the Galilee of

Jesus. We know that he was of noble Semitic lineage and he was

raised in a family business of Tektons. He had four younger

brothers and at least two younger sisters, an issue we'll cover

below.

Jesus' trade

Matthew 13:55 describes Jesus as "The carpenter's son,"

O TOU TEKTONOS UIOS, tekton being rendered as

"carpenter" in translation. The Aramaic would have be berah

d'nagora. More accurately, it is an

artificer who could work in wood, fabric, masonry, sort of a

general contractor or builder. Certainly carpentry would have

been the most common undertaking. As the oldest son, Jesus would

have been important to the family business and each of the sons

may have had a specialty. The Galilee and the Decapolis (Ten City

region) was an area of intense building projects and probably

supplied more than enough work for the family. Tradition has it

that Jesus was famous in this farming region for his yokes and to

own one was a point of pride. There is no actual reference to

Jesus himself as a carpenter and the earliest papyri refer to him

as the Carpenter's son.

Some scholars suggest that Jesus was not a carpenter himself but

was, in fact, a magician, having learned magic in Egypt. This is

an ancient argument going back to early polemic against

Christians and is mentioned by the second century Christian

apologist, Justin Martyr(8) and the second century Platonist,

Celsus. Celsus work, an attack on Christianity has not survived

but was answered around 247 CE by the Christian apologist,

Origen.(9) The opinion that Jesus was not a carpenter, but a

magician, is expressed in an impressive modern study by Morton

Smith.(10) The viewpoint that the author of Matthew invented the

story of the sojourn into Egypt to provide an argument against

the polemic against Jesus as an Egypt-educated Magician (another

of those "white lies") is another scholarly opinion

that this layman cannot accept. In first century Galilee, the

oldest son would almost certainly follow the trade of his

father.(11) I believe that the young Jesus worked at his father's

side and with his brothers in the family contracting business

until he launched his ministry. That Jesus waited until the year

26 or 27 to begin his mission suggests to me that Joseph had died

and it was no longer a demonstration of disrespect to leave the

family trade. Giving all due respect to the learned scholars,

this layman must again conclude that the Gospel account is

correct.

Jesus' Language

We cannot tackle the more difficult issue of what Jesus' exact

words were without a better understanding of the language in

which it was rendered. The Gospels and books of the New Testament

were set down in Greek between 20 and 80 years after

they were spoken. Greek was the vernacular of the West and the

language of commerce. The vernacular of the East, and Jesus'

language, was Aramaic.

The Hebrew language in first century Palestine was used for

scriptural and scholarly writings. The weekly synagogue readings

(the Sidra, Parashah,

and Haphtarah) were

always accompanied with an Aramaic translation. These oral

translations of the Hebrew lections to Aramaic would eventually

be written down in the Targumim.

The Gemara of the Jerusalem

Talmud and the Babylonian

Talmud were written in Eastern (Babylonian)

Aramaic.

Why did the Jewish people speak Aramaic and not Hebrew? Aramaic

was the language of commerce of the Persian Empire and was used

widely from the Indus Valley to Egypt. It became the language of

the Jewish people by conquest first when the Israelites were

deported by Tiglath-Pileser III in 732 BCE in the first Assyrian

invasion. The northern tribes were deported in 721 B.C.E. when

Sargon II made Israel an Assyrian province and finally the

Judeans were deported in 587 B.C.E. by Nebuchadnezzar. There is,

in a sense, some irony to this since these Mesopotamian

conquerors came from the land that gave birth to Abraham. Aramaic

was the language of the ancestor of the Jewish people. What is

known as the Hebrew Language

in the New Testament was called the Lip of

Canaan in the Old Testament. Abraham and the

Patriarchs adopted the language and script of the Phoenicians.

The aftermath of the Babylonian Captivity resulted in a

readopting of the Aramaic ancestral language of Abraham. The

"Hebrew" script used today is actually the Aramaic

Square Script, which replaced the Phoenician script known as

"Old Hebrew" about 200 B.C.E. Old Hebrew is exemplified

by the Moabite stone inscription, the Lachish letters, and the

Siloam inscription. Most Christians are surprised to learn that

until the adoption of Hebrew as the official language of the

State of Israel in 1948, it had not been the vernacular of the

Jewish people for over 2500 years.

Jesus' name in his own Aramaic language was Y'shua

bar Yosef (Ye-SHOO-ah bar Yo-SEF). He spoke

Aramaic when he preached or had conversations with his family,

friends, and disciples. He would have used Hebrew in

conversations with religious leaders and is recorded in the

Gospels reading the Hebrew scriptures of Isaiah in the synagogue

at Nazareth (Lk. 4:16-19). As a tradesman, working with his

father and brothers on various building projects, he would have

had to have some knowledge of Greek, the language of commerce. It

is debated by scholars whether or not he was fluent in Greek or

used it for any purpose outside of trade. It is this author's

belief that he was well-educated, functioned well in Hellenistic

surroundings, and probably was fluent but may have considered it

the "gentile tongue" and eschewed it for common usage.

What type of Aramaic did Jesus speak? Aramaic ceased to be a

uniform language during the anti-Semitic period of the

Hellenistic Seleucids prior to the Maccabean revolt. During this

period various dialects began to form on a regional basis, each

with variations in pronunciation and vocabulary. These influences

caused Aramaic to divide into a Western

Branch with several dialects and an Eastern

Branch with its dialects. The five periods

of Aramaic, dating from 1000 B.C.E., are as follows:

Old Aramaic 1000 BCE to 700 BCE. Imperial (Official) Aramaic 700 BCE to 200 BCE. Middle Aramaic 200 BCE to 200 CE. Late Aramaic 200 CE to 700 CE. Modern Aramaic 700 CE to present

Jesus spoke the Galilean dialect of Middle Western Aramaic. The

Galilean dialect was recognizable by Judeans much as a deep south

dialect of English is recognized in the United States. Likewise,

the Galilean dialect was considered provincial by the Judeans.

Galileans had a tendency to drop the gutturals much like the

Cockney "Enry" for Henry. An initial aleph was usually

dropped, which explains why Jesus' good friend Alazar

was called `Lazar by

Jesus and eventually Latinized in the Vulgate to Lazarus.

It is also why Simon Peter was recognized as a Galilean outside

of the house of Caiaphas.

After a little while the men standing there came to Peter.

"Of course you are one of them," they said. "After

all, the way you speak gives you away!" Matthew 16:73

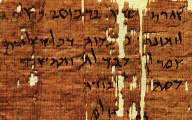

An Aramaic letter from Simon

bar Kochba to Yehonathan bar Be'aya, written during the Jewish

revolt 132-135 CE.

Jesus'

Education